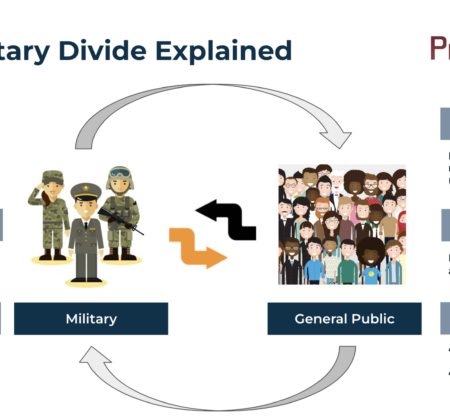

So what does the elephant in the room have to do with military transition, you ask? Well, quite a bit more than you may think. Following my own transition experience, I’ve taken the better part of the past five years studying the current transition system and associated outcomes.

Based on my research and personal experience, I offer two takeaways from the fable:

- I believe we’ve completely missed the elephant in the room for the past 30 years: despite existing transition programs, the first two years following military transition remain problematic and need to be addressed.

- If we don’t effectively address that two-year period following military transition, we’ll continue getting poor outcomes for transitioning military members.

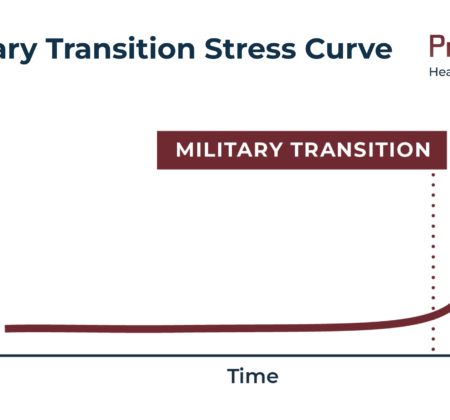

The Challenging Two-Year Period Following Military Transition

To reiterate, the data from 1991 through 2020 indicate military transition has been and remains problematic. This is particularly true with respect to employment; however, the data is also a bit more nuanced and needs to be understood within the proper context. For example, here are three research artifacts that span 30 years of data which indicate consistent problems with chronic unemployment and poor retention. Research includes two U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs–funded studies and one Pew Research Center survey with the following details:

Regarding unemployment:

- A 2008 study found that from 1991 through 2003, recently separated service members (RSS) had, within two years of separation, higher rates of unemployment compared to the general public control group. On average over the period, the RSS unemployment rate was two times the control group.

- A 2015 study which in part examined unemployment claims found that from 2004 to 2012, between 29% and 53% of all veterans have a “period of unemployment” within the first 15 months after departing the military. Furthermore, the number of consecutive weeks they collected unemployment grew from 18 to 22 weeks in 2013.

- Most recently, a 2019 Pew survey indicated that 25% of transitioning members had a job lined up, 48% looked for a job right away, and only 57% had a job within six months. The study did not determine whether or not those within the 25% surveyed who said they had a job lined up following transition actually got those jobs.

Regarding poor employment retention:

- A 2014 study noted that 50% of transitioning service members left their first job within one year and 65% left within two years. For a point of comparison, on average, the general public within the labor force changes jobs every four years.

- According to the 2019 Pew survey cited above, 44% of transitioning military leave their jobs within one year.

The Rebound

While there are undeniable unemployment and retention challenges in the first two years following transition, things change after those two years. This where the data gets nuanced because veterans begin actually outperforming their general public counterparts after those two years.

Two metrics capture this phenomenon:

- Overall veteran unemployment rate: According to data from 2003–2019 published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, overall and with no exceptions, the veteran unemployment rate has always been lower than that of the general public.

- Median income: According to the 2015 Department of Veterans Affairs study cited earlier, veteran median income is $10,000 higher than commensurate non-veterans. This particular study cited data from 2005–2014.

These two very different outcomes explain why the data is so nuanced. While the first two years following military transition are challenging and problematic, veterans overall make a solid recovery following that two-year slump.

Which raises a fundamental question: Shouldn’t we be zeroing in on and trying to correct that challenging two-year period following transition?

The Best Way to Address the Two-Year Period

How to best address that challenging two-year period should be an open conversation for stakeholders in the transition community.

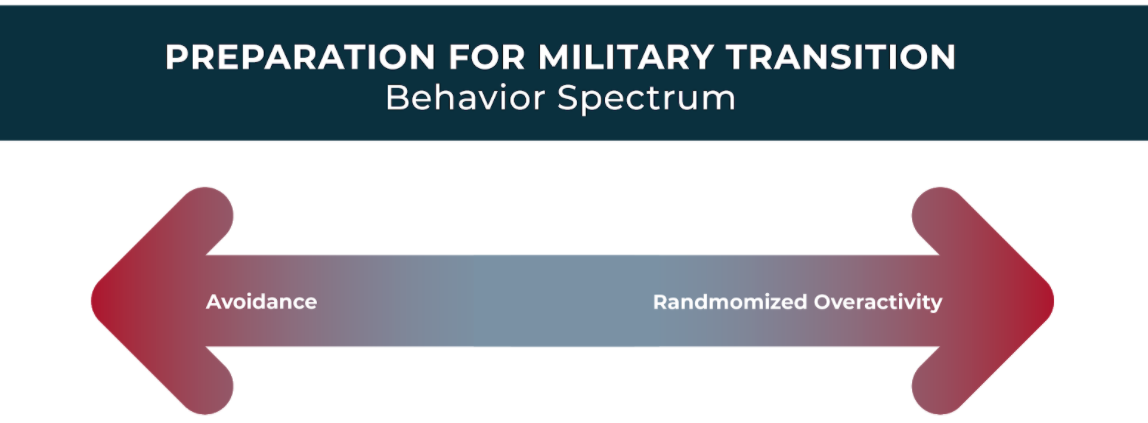

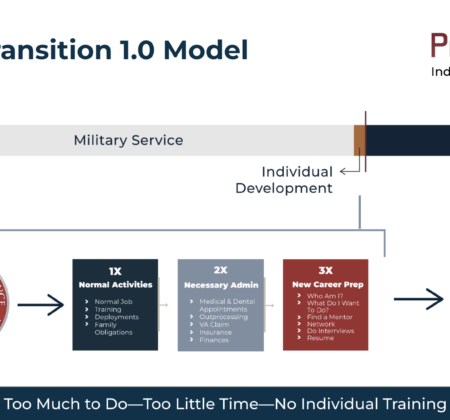

At PreVeteran, we believe the best way to address that period is to provide the framework, individual tools, and support to help the transitioning military member plan their own unique transition—well before they take off their uniform. By doing so, they begin a personal self-transformation that helps them become much more aligned with the private sector’s needs and wants.

Being better aligned with the private sector’s needs and wants means transitioning military members can find the job they want and make more money—all the while creating more certainty and stability in their approach, not to mention happiness and security for their families.

If you are a transitioning military member, you can get started today by doing the following three things:

- Download our free “5-Step Guide to Finding the Job You Want, Post-Military.”

- Subscribe to our PreVeteran YouTube channel.

- Follow PreVeteran on LinkedIn.

Sources:

W.R.S. Ralston, trans. M.A. Krylof and His Fables. Translated by W. Ralston. London: Strahan and Co., 1869. https://archive.org/details/krilofhisfables00kryl/page/n21/mode/2up

Abt Associates Inc. “Employment Histories Report: Final Compilation Report.” March 24, 2008. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SurveysAndStudies/Employment_History_080324.pdf

Department of Veterans Affairs. “2015 Veteran Economic Opportunity Report.” 2015. https://www.benefits.va.gov/benefits/docs/veteraneconomicopportunityreport2015.pdf

Pew Research Center. “The American Veteran Experience and the Post-9/11 Generation.” September 10, 2019. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2019/09/10/the-american-veteran-experience-and-the-post-9-11-generation/

Syracuse University Institute for Veterans and Military Families and VetAdvisor. “Veteran Job Retention Survey Summary.” October 2014. https://ivmf.syracuse.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/VetAdvisor-ReportFINAL-Single-pages.pdf

Blue Star Families, “2018 Military Family Lifestyle Survey—Comprehensive Report.” Blue Star Families, 2018. https://bluestarfam.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2018MFLS-ComprehensiveReport-DIGITAL-FINAL.pdf

Mary Keeling, Sara Kintzle, and Carl A. Castro, “Exploring U.S. Veterans’ Post-Service Employment Experiences,” Military Psychology 30, no. 1 (2018): 63–69. https://cir.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Exploring-U-S-Veterans-post-service-employment-experiences.pdf

Sara Kintzle, Janice Rasheed and Carl Castro. “The State of the American Veteran: A Chicagoland Veterans Study,” USC School of Social Work, Center of Innovation and Research on Veterans & Military Families, 2016. https://cir.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/CIR_ChicagoReport_double.pdf