Why Military Transition 1.0 Has Let Us All Down (Part 1 of a 3-Part Series)

May 31, 2022

- Since 1991, a group-focused transition assistance program (TAP) has dominated the landscape but with lackluster results because the individual is completely absent from the methodology. Here are a couple highlights of those lackluster results for transitioning military members within two years of separation or retirement:

- Employment: extended periods of unemployment, underemployment, poor retention, low starting salary

- Higher Education: poor academic persistence rates, 48% graduation rate

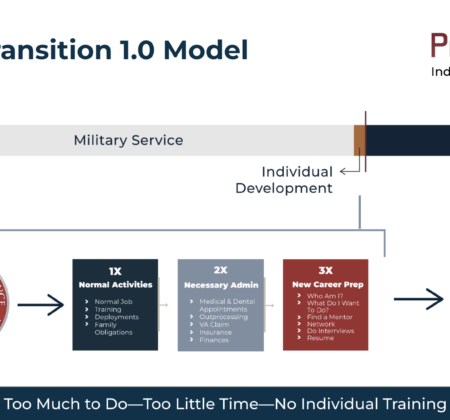

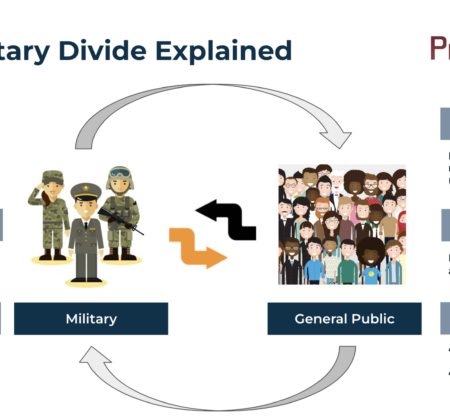

- Because the transitioning population is about 220,000 service members per year, it’s understandable that the government created a group-focused program. From their perspective, how on earth can they take into account every individual’s journey once they leave the military? It’s much easier to take individuals from the general U.S. population and turn into into soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines than to do the opposite—return those deep-seated groups back into individuals. In addition, because the government has a fiduciary responsibility to provide “transition services” to all service members, they must literally cover EVERY transition scenario in their one-week training period.

- In its current format, TAP is supposed to begin no later than one year prior to transition (no later than two years for retirees) and begins with what they call Individualized Initial Counseling (IC) where “service members complete their personal self-assessment and begin the development of their Individual Transition Plan to identify their unique needs of the transition process and post-transition goals.”

- Following the IC, the member begins their pre-separation counseling, which follows this DD Form 2648 pre-counseling checklist. Simply peruse this checklist for a moment and you’ll get a firsthand look at what a group-focused program looks like.

- Another thing worth noticing on the checklist is the beginning of what we call the resource dump—a true hallmark of a Military Transition 1.0 program. And where you can view the links to resources on the checklist itself, the resource dump continues as each and every service member goes through the congressionally-mandated TAP Curriculum.

- Through this lens, it’s hard to look past the reality that this “training” is nothing more than them hosing you down with resources and hoping some of them stick.

- For those of you who have been through TAP, you know what this feels like. You sit intently through a week’s worth of classes covering everything under the sun for the 5% of information that’s germane to your individual situation.

- Here’s the problem with this approach—the lack of stickiness of the

material they provide. To explain this, let’s venture into education principles for a moment to make the point that all learning is contextual. This means that in order for the subject matter to be processed by the student and used in the desired domain—in this case something as important as their life after the military—the individual receiving the information has to know how that information is used and where it fits into their own unique journey.

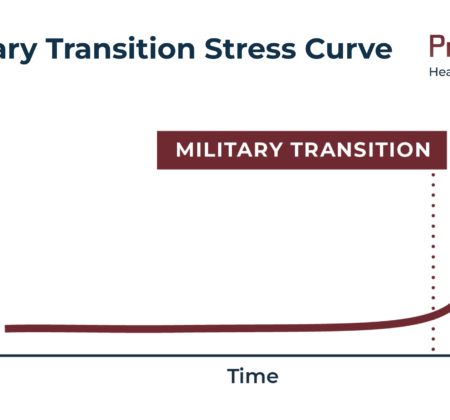

material they provide. To explain this, let’s venture into education principles for a moment to make the point that all learning is contextual. This means that in order for the subject matter to be processed by the student and used in the desired domain—in this case something as important as their life after the military—the individual receiving the information has to know how that information is used and where it fits into their own unique journey. - Otherwise, without context, the individual will not know how to use those resources and, as the graphic shows, no matter how many resources are provided, they will never be enough. This results in the very undesirable lose-lose scenario.

- From here, you can take a step back and see that this is the granny gear we’ve been stuck in for three decades when it comes to military transition.

- While TAP is less than effective (to be nice) or ineffectual (to be real), it’s actually worse because, despite its ineffectiveness, the program has essentially been institutionalized, which has created two problems.

- First, to use a 2008 financial crisis cliche, it’s too big to fail, which is to say that we should expect the same poor outcomes we’ve always gotten and continue to throw good money after bad.

- Second, exacerbating and reinforcing the ineffective system are secondary and tertiary markets that have developed using the same flawed methodology. These markets include innumerable nonprofits that provide transition services and recruiting firms who typically zero in on particular MOSs or AFSCs who they feel will deliver the largest return on their time investment.

- The unfortunate reality is that these secondary and tertiary markets are built upon a faulty Military Transition 1.0 foundation. If the system worked well, we should expect to see significant progress in the transition through the employment, higher education, and wellness aggregate numbers—but we don’t. As we briefly touched on earlier, we continue to see very lackluster performance for the first two years after leaving the military. Over a 30-year period, the numbers have stubbornly stayed the same and in some cases, have actually worsened.

- So, it should go without saying that Military Transition 1.0 is not working and needs to go for one simple reason: it hurts individual service members and their families, which will eventually hurt military recruiting in the years to come. After all, who would want to go into the military—or what parent would want their child to go into the military—knowing there’s a strong possibility he or she will come out of the military worse off than when they went in?

Read Part Two of the Series—The Cognitive Response to Military Transition 1.0