The Cognitive Response to Military Transition 1.0 (Part 2 of a 3-Part Series)

May 31, 2022

- To start on a positive note, I’d like to say that I believe the transitioning military population is a very high-functioning, educated, and driven group of individuals that could add significant capabilities to the national workforce; unfortunately, as we also discussed, the current Military Transition 1.0 system is not producing this desired result.

- While it would be easy to simply place three decades of poor transition performance at the feet of the Military Transition 1.0 system, that would do nothing to fix the problem. As we’ve discussed, the system itself is now highly institutionalized, with embedded secondary and tertiary markets in place, and will not change. But there’s also another element that needs to take center stage if we really want things to change: fully understanding the individual service member’s cognitive response to the Military Transition 1.0 system.

- To begin this discussion of what’s happening in the service member’s mind, we need to make a very obvious statement: at the end of the day, each and every transitioning military member’s transition will be profoundly individual. Which is to say, at a cognitive level they need to think through the steps they need to take to be successful.

- You may already be asking yourself this question as you read through our argument: How does one think through their own unique military transition if they’re only provided group resources? Well, judging by 30 years of data, the obvious answer to that question is: Not very well at the moment.

- To support a high-level explanation for why this is happening within the minds of our transitioning military population, I need to provide you some context so that this information sticks with you.

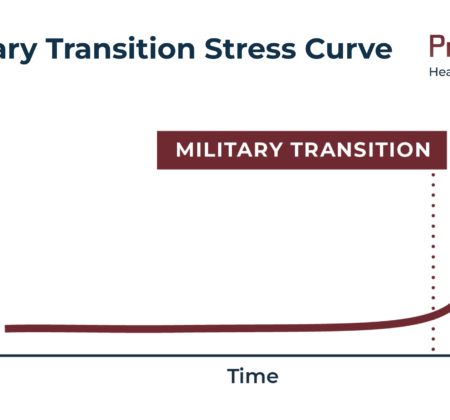

- First, as the founder of PreVeteran, I did two years of research to discover that there was a two-year poor performance gap following the military transition. Soon after finding that gap, I wanted to figure out why the gap was occurring.

- It’s a long, non-linear story, but keeping it short for the purposes of this series of articles, and after looking into several different academic disciplines, I landed on cognitive neuroscience for one simple reason: there is nothing more profoundly individual than understanding how every person’s brain processes information from the external environment to derive thought, behavior, and ultimately action.

- While I was very taken with the idea because it just made sense, I was certainly not an expert in the field, so I consulted with a cognitive neuroscientist for an entire year. She was wonderfully knowledgeable on the subject, and while I learned a lot over that year, I grew increasingly frustrated by how narrow the views were in academia. For example, when I asked questions that did not land precisely in her field of expertise, she told me to “find a sociologist” or “talk to a psychologist.”

- Driven by that frustration, I elected to take a new approach. I decided to build my own model based on cognitive neuroscience principles and have her validate the model. It worked and became the bedrock of our PreVeteran ecosystem and programming.

- With that as a backdrop, let’s get into some high-level concepts to explain what’s occurring in the minds of our transitioning service members as they try to process information coming out of the Military Transition 1.0 system.

- First, we need to tell you a bit about how brains function. The important thing to remember here is that while the brain is an amazing organ, it is subject to vulnerabilities as it functions in its normal state.

- To start off, there are many brain attributes; however, for the purposes of this article, here are the ones that are germane to this topic.

- The brain:

- Serves the individual and ensures their survival by processing information to help that individual make decisions in navigating their lives

- Constantly seeks speed and efficiency in its processing by creating heuristics, neurological shortcuts in the brain which allow for the individual to arrive more quickly at decisions or make judgements created by enduring, long-term memories

- When confronted with a sensory input, will make associations between that input and existing long-term memory

- Serves the individual and ensures their survival by processing information to help that individual make decisions in navigating their lives

- Based on this very limited amount of information on brain attributes, one can already get a sense of how such an amazing organ can create serious thinking vulnerabilities for the transitioning military member.

- Let’s look for more and better detail. To do this, PreVeteran would like to add new words to the military transition space that explain existing behaviors found in anecdotal conversations and throughout the transition research landscape.

- You can see from the brain’s attributes above that accessing and using long-term memories play a big role in the thinking process.

- To point out where things begin to go wrong with military transition specifically, let’s use the following example. A simple self-generated thought from the service member asking him or herself, “How should I get ready for military transition?” This is where the problems begin and are then exacerbated by the Military Transition 1.0 system.

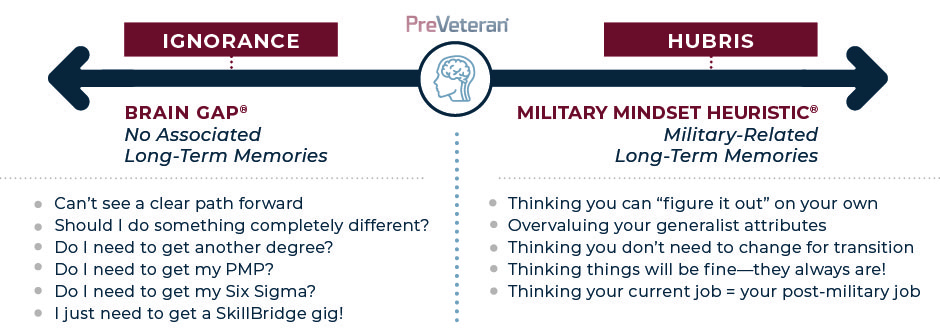

- As you can see in the graphic above, transitioning military members have long-term memories ranging from zero to a plethora of military-related long-term memories. (Spoiler alert: both ends of the long-term memory spectrum create problems!)

- As a topline statement, military members (and their spouses or significant others) approach their decision making from either ignorance or hubris.

- Let’s start with ignorance, which we call the Brain Gap. The Brain Gap occurs when the transitioning military member has no long-term transition-related memory to draw from that will help him or her transition to a new and demanding ecosystem.

- In research articles, transitioning service members articulate that as not being able to see a clear path forward, which is extremely frustrating and stressful for the military member who’s used to being able to clearly see from point A to point D on countless missions they have performed, in complex and often dangerous environments, while they were in uniform. Despite those experiences, they’re unable to do that now because there are no long-term transition-related memories to draw from and as a result, thinking stops in its tracks.

- So, harkening back to one of the brain’s attributes—ensuring one’s survival—the brain will sense that gap and then seek information that seemingly fills that gap in the external environment.

- This is where the messaging from the Military Transition 1.0 world enters the equation, because the separating member’s brain is in search mode. For those of you familiar with the military transition space, the following is the steady drum beat of messages coming from the 1.0 community and stakeholders.

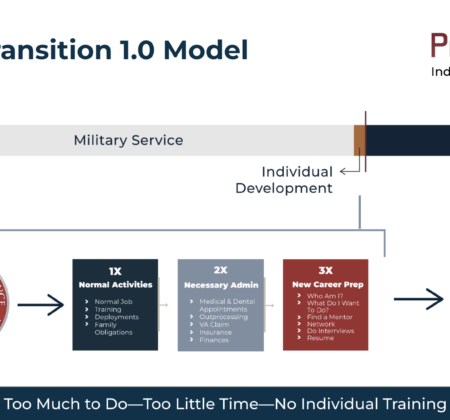

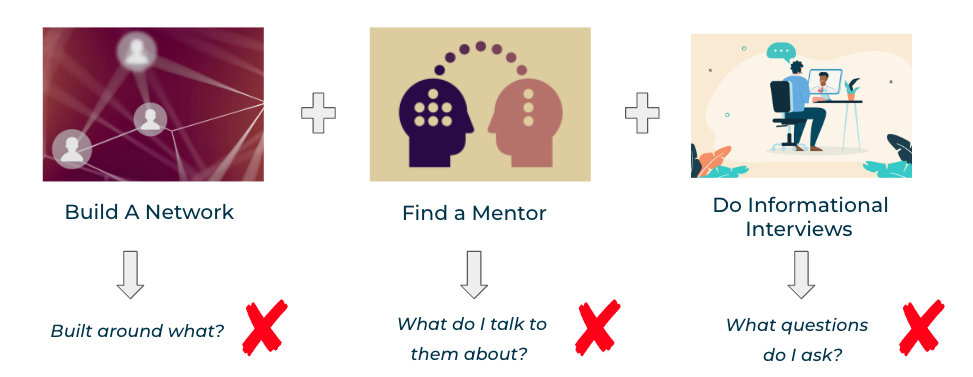

- They’ll tell you to build a network (actually sometimes they go as far as saying, “Network, network, network … and when you’re done, network some more!”), find a mentor, and do informational interviews.

- In fact, one very prominent influencer told his audience it could take up to 200 cups of coffee doing informational interviews to put you in a good position to figure out what you want to do employment-wise, post-military. Yikes! Does this sound like a good plan? Who’s got the time to do this?

- But this is the insidious nature of the military transitioner’s mind when it’s seeking—and in many cases using—the inputs from the 1.0 system and its stakeholders.

- By looking at the graphic, you can see the house of cards created by the 1.0 messaging. One only needs to ask one simple question on each topic to reveal its weakness. What should I build my network around? What should I talk to a mentor about? What questions do I ask an interviewer?

- Considering these questions, you can see how the system and its influencers, through a lack of appropriate and decisive focus, arrive at the flawed conclusion that one must have 200 cups of coffee to somehow get going in the right direction.

- And that’s just the Brain Gap®—while it creates noise and confusion in the transitioner’s mind, the other side of the long-term memory spectrum causes equal, if not more, harm.

- Let’s talk about the Military Mindset Heuristic®. MMH is the result of having a plethora of military-related long-term memories the transitioner will inevitably draw from when making decisions about life after the military. In other words, they use their military-related long-term memories to draw from when making decisions on the transition from the military ecosystem to public life.

- Because the human brain depends on lived experiences (in the form of long-term memories) to draw from, it will consistently draw from that deep reservoir of memory to help make life decisions.

- And it will draw from two of the memory’s pathways: normal memory recall or heuristic recall. Here’s the slight difference and it goes back to the brain’s attribute of wanting to be efficient. In normal memory recall, mechanisms within the brain will seek and draw associated memories.

- The heuristic is developed when the individual has repeated the same line of thinking so many times that having that thought pop into your mind happens automatically and without conscious thought.

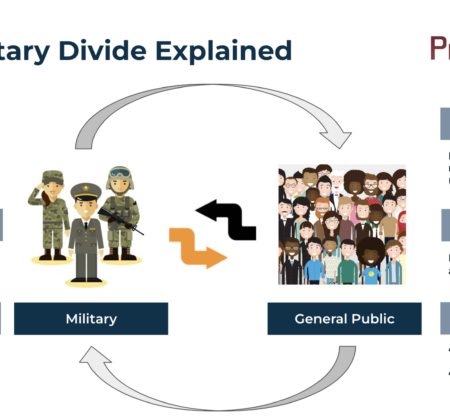

- The real problem, whether it’s normal memory recall or the more automatic heuristic mode, is that the military and civilian sector environments could not be more dissimilar. This creates a fundamental misalignment between what’s in a separating member’s mind and what the private sector’s needs and wants are.

- Perhaps the most pernicious aspect of this disconnect is that every member’s mind is trying to make these decisions—and the result can be confusion. As a general rule of thumb, humans tend to listen to the messages their minds are telling them, particularly when it comes to something as consequential as their life trajectory.

- To paint a clear picture of challenges coming from the Military Mindset Heuristic, let’s briefly discuss the following: overvaluing their generalist attributes and thinking they don’t need to adapt to the demands of post-military employment.

- Remember, the Military Mindset Heuristic occurs when one’s brain tries to pull away from long-term, military-related memories. Well, for those of us that have worn the uniform, we can tell you that the Department of Defense, regardless of service, will put you where they need you within the unit, regardless of your Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) code or Air Force Speciality Code (AFSC).

- Over years, and perhaps decades, the repetitive nature of this reality equates to countless cognitive iterations that create memories. And these memories, when drawn upon, or bypassed altogether via the creation of a heuristic, will convince the transitioning individual that the private sector will value their generalist attributes.

- Anyone who has worked in the private sector will tell you that this thinking process is diametrically opposed to how private sector employers staff their companies. Private sector companies have a head count to fulfill; they hire credentialed individuals with a specific skill set to fill a very specific role in the organization. The private sector does not ordinarily look for generalists.

- Now let’s talk about transitioners thinking they don’t need to change. They may not recognize the stark reality that while serving in the military active component, they represent less than 1% of the U.S. population. When they become veterans, they’ll ultimately need to interact and work with the 93% of the U.S. population that is not veteran-affiliated And guess what? They think a bit differently because they have different experiences to draw from. So, they need to change and to better understand the private sector’s needs and wants if they want to be successful, no matter what they want to do when they separate or retire.

- Where the Military Transition 1.0 system constitutes the external environment from which the individual transitioning military member must emerge, we hope you can begin to see how these two systems play off one another to create poor outcomes for our military members and their families. In our final article of the series, we’re going to provide you a solution to this situation—something we call Military Transition 2.0.

Read Part Three of the Series—Why We Need to Move to Military Transition 2.0