This article was published in Military.com. Article link can be found below article.

Your base-level Transition Assistance Program (TAP) class does what it can. The Department of Labor says an estimated 180,000 personnel leave the military every year, and with so many people in need of access to resources, transition information and job search training, TAP classes are tapped as it is.

They can also be detrimental to positive outcomes for some of the service members they’re trying to help.

Liz Roumell is an associate professor of educational administration and human resource development at Texas A&M University. She is also a leading researcher for PreVeteran, a military transition training and mentorship company. She says that while traditional transition assistance classes are necessary, they may compound some of the problems military members have during that critical time period.

“Military transition classes are a system-built program,” Roumell tells Military.com. “It has to be done, but with so many people transitioning every year, it also has to be scalable and fairly consistent across the board. So it’s built like most training programs: Here is your information. Here are the resources.”

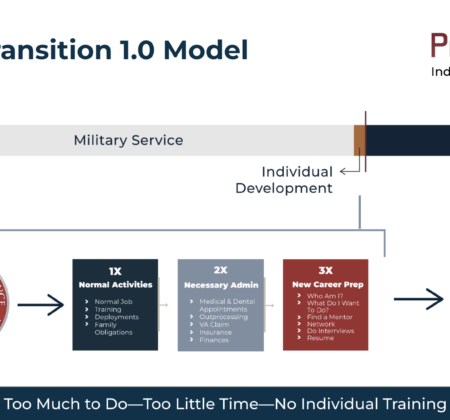

The problem with what she and PreVeteran refer to as this “Transition 1.0 Mindset” is that it’s not necessarily meaningful for the individual. Simply put, there’s no context for an individual service member to apply the information to their personal and professional goals — if they even know what those goals are.

“Processing checklists are very appropriate for that kind of program,” says Roumell. “They recognize that resources are necessary and that finding employment is necessary. But that kind of program doesn’t change someone’s mindset. I don’t know if it even recognizes that mindset is part of the transition process.”

When people go through a major life change such as exiting the military, stress can cause strong biological changes. Weight gain or weight loss brought on by the duress of the situation can radically alter moods, along with what Roumell calls the emotional and social labor of transition.

Emotional labor refers to the actual mental work behind everything involved with leaving the military, from setting goals and pursuing them to ensuring support for spouses, partners and children, along with everything in between. Social labor is the need to rebuild personal and professional networks and relationships as the veteran moves into a new city, neighborhood, career and/or culture.

Military personnel, Roumell says, are highly functioning individuals, capable of a lot and confident in their abilities, but this kind of transition can have an adverse effect on anyone.

“It requires a lot of extra work to rebuild these resources for yourself,” she says. “Our cognitive bandwidth is only so much, even when we’re at our best with no stress or duress. When you get this long checklist and dump of information thrown at you as you’re being pushed toward the door, along with everything else you’re supposed to take care of in such a short time, it takes a toll on you physically.”

When overwhelmed with information their brain can’t make sense of, people begin to default to applying the new information systems and processes with which they are already familiar. Roumell and PreVeteran call this the “Brain Gap,” and it’s a natural process people use to make the influx of information more useful.

When people start moving into a context different from what their current situation, such as a military to civilian transition, knowledge gaps form. When presented with a sudden, large amount of information without individual context, such as the TAP classes’ dump of information, the brain relies on its previous knowledge and experiences to fill that gap.

“Most of our behaviors, actions or decisions are based on our experience and our memories of those experiences,” Roumell explains. “We build these patterns in our mind and use them when presented with gaps of information. Our most natural thing to do as human beings is to take the next closest thing and fill the gap with that.”

In a transition context, this means veterans without clear goals and directions will use their group-oriented military mindset when dealing with the civilian business world, a mindset that PreVeteran founder and Air Force veteran Jason Anderson says doesn’t work very well.

“The military system is created for the military,” Anderson says. “These two systems are different, yet we still convince people that they’re gonna be like seamlessly moving over into a different world and context. Veterans are a highly functional group of people: very educated, very driven. But they need to be told the limitations of the thinking they bring into the general public.”

According to PreVeteran’s research, the military’s active component represents just 1% of the population and is going into a world filled with the 93% of Americans who have no first-hand military experience. They think differently because they have different experiences. Civilian employers want experts in their field. Civilian workers tend to be individually oriented. This mindset runs counter to the military’s generalist training and group-oriented structure — and that’s just the beginning.

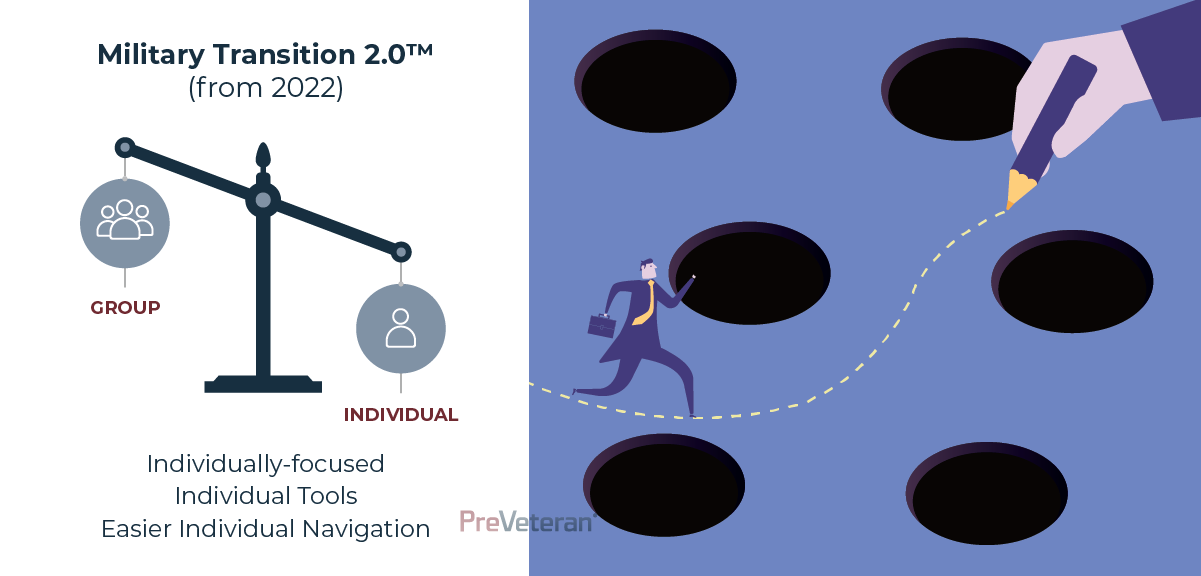

The solution Roumell and Anderson found for the PreVeteran course is what they call the “Transition 2.0 Mindset.” Veterans need to set goals individually and tailor their transition information to those goals.

They also need to adjust the way they think to meet the needs and expectations of the civilian world. Finally, veterans need to allow themselves time to change their mindset, process this information, set those goals and chart their way forward as an individual.

Read: The Case for ‘Transition 2.0’ and What It Should Look Like for Separating Veterans

Without individually set goals and a specific plan to meet those goals, TAP’s lessons in creating professional networks, getting a mentor or doing informational interviews will be random shots in the dark. A structured plan allows for building specific networks, finding a mentor in a desired field and making informational interviews with experts more informational.

“Becoming aware of your thinking patterns is like a superpower,” Roumell says. “It’s powerful because it can be applied to your military transition, but it can also be used across many different contexts. If you can understand your own thinking, you can control the situation and you can take real forward action, and that’s really important.”

To learn more about PreVeteran and the Transition 2.0 Mindset, take the Employment Readiness Quiz or read the 5-Step Guide for Getting the Job You Want.

— Blake Stilwell can be reached at blake.stilwell@military.com. He can also be found on Twitter @blakestilwell or on Facebook